Afgelopen vrijdag sprak Fanie du Toit de tweede BKB Lezing uit in de Duif aan de Prinsengracht in Amsterdam.

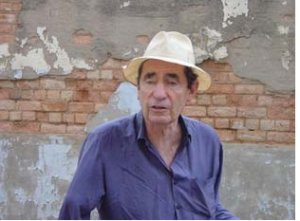

De Zuid-Afrikaan Fanie du Toit (1966) is directeur van het Institute for Justice and Reconciliation dat in 2000 is opgericht om voort te bouwen op het werk van de Zuid-Afrikaanse Waarheid- & Verzoeningscommissie.

In zijn lezing getiteld: Relativism, Reconciliation and Reality reflecteert Du Toit op verschillende aspecten van ethische politiek in verdeelde samenlevingen. Hoe gaat Zuid-Afrika om met zijn verleden van apartheid en rassenscheiding? Hoe verwerken andere Afrikaanse landen de trauma’s van oorlog en genocide? Hoe leg je weer een verbindingen in een samenleving die totaal is ontwricht? En wat zijn de lessen van voor de wereld van ná 9/11?

De gehele lezing, evenals het co-referaat van voormalig staatssecretaris Frans Timmermans is hier te downloaden.

Eén verhaal over Albie Sachs wil ik graag uitlichten, omdat het tijdens de lezing bij mij voor kippenvel en tranen in mijn ogen zorgde:

[…] If South Africa’s reconciliation process was, at heart, not sentimental, it was also not cheap or, in the words of Archbishop Emeritus Tutu, it was never cosy. Contrast Mac’s story of shrewd pragmatism and hardnosed realism with that of retired Constitutional Court Judge, Albie Sachs.

For leaders such as Sachs, reconciliation was not in the first place seen as ‘a smart move’ or pragmatic choice. It was primarily an ethically correct choice – an ideal inscribed in the DNA of their politics.

Recently the Institute for Justice and Reconciliation bestowed its annual Reconciliation Award on Albie Sachs. Sachs was present in Kliptown near Johannesburg in June 1955 when the Freedom Charter was adopted, declaring ‘for all our country and the world to know that South Africa belongs to all who live in it, black and white’.

Sachs once famously called for ‘soft vengeance’ in defence of a political ethic that would seek to overcome the apartheid enemy through a moral victory rather than a military one. The bigger victory would not be to overthrow Pretoria through military might, he argued, but to force advocates of apartheid to live in, and accept, democratic values. Democracy would be the ultimate (soft) vengeance against apartheid.

Apartheid’s response was less compromising. In 1988 a bomb planted by an apartheid operative in Mozambique very nearly ended Sachs’s life. While recovering, and having lost his right arm, he learnt to write again with his left hand. Most people would seek retribution, some way of ‘teaching them a lesson in the language they would understand’. Sachs instead began to draft South Africa’s first democratic constitution in hesitant, almost childlike script. For Sachs, the future depended on supplanting racism with reconciliation and social justice that showed no patience for entrenched inequality. It depended on creativity, selflessness, and a good sense of humour. Despite the terrible cost, apartheid crimes were not allowed to set the tone for the transition. In this manner, the way from macho-politics to ethical politics was beginning to be forged.

In 1990, after Sachs returned to South Africa from exile, he devoted himself fulltime to preparing for a new democracy, including making arrangements that eventually paved the way for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). After the elections of 1994, President Mandela appointed him to serve in the newly established Constitutional Court. As judge, Sachs became a chief author of post-apartheid jurisprudence, producing several important rulings which are helping to reshape the South African landscape. He has played a pivotal role in developing the Constitutional Court building as well as its art collection – with the aim of turning both into a symbol of African heritage and of an open, people-centred and inclusive ethos. His legendary tours of Constitution Hill have introduced thousands of visitors to the court and its mission. He retired from the Constitutional Court in 2009. […]